AMP Capital Economist, Diana Mousina's latest Econosights note looks at the state of the Australian infrastructure pipeline, and asks: is it as good as it gets?

Over recent years, there has been increased talk from global policymakers and organisations (like the International Monetary Fund) about the need to lift infrastructure investment, especially across the advanced economies. Infrastructure investment refers to spending on buildings and structures that form the systems of a society (for example transportation, water and electrical systems, hospital buildings) which are led by the government (federal or state).

The recent focus on growing infrastructure investment has come about because:

- The limits of monetary policy have been reached after central banks cut interest rates to record lows started quantitative easing, stimulating consumer spending and asset price growth. But, the impact on other parts of the economy (such as investment) has been softer because monetary policy has less of a direct impact on these areas.

- GDP growth in the advanced economies has been below its long-run average since the financial crisis (until recently) which has kept inflation below central bank targets. As a result, there is a need to lift growth and bring inflation back to its target rate.

- Borrowing costs are low because interest rates have been cut substantially to stimulate growth which is good for potential government borrowing.

- There is a need to replenish the capital stock as it ages to improve productivity growth and living standards, lift economic progress and development.

What has happened in Australia?

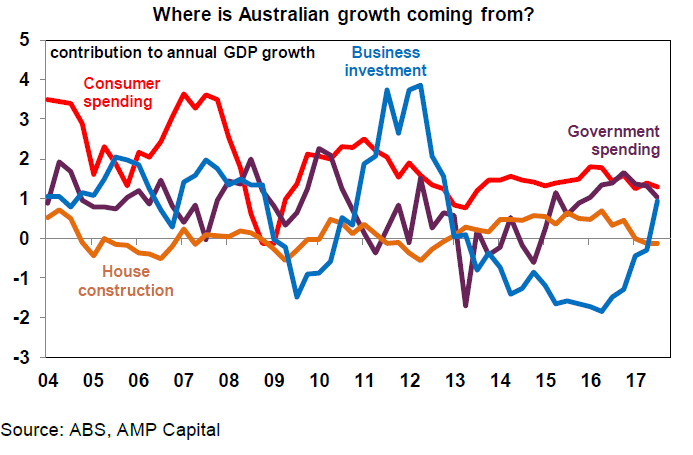

In Australia, infrastructure spending has been declining as a share of GDP growth in recent years, similar to our global peers.

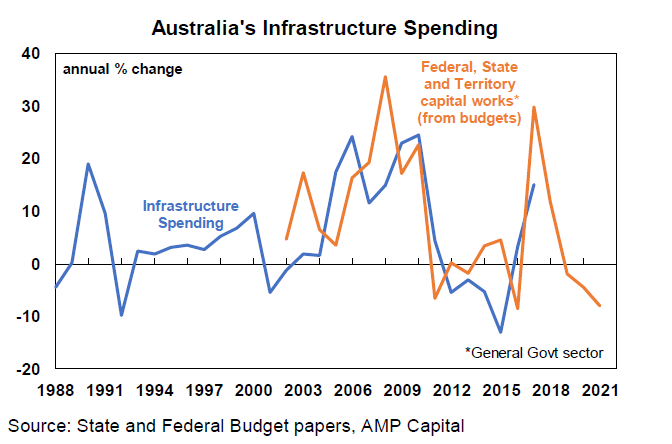

But, since 2016, infrastructure growth has been bouncing back thanks to a lift in Federal government spending and buoyant state budgets (particularly in New South Wales and Victoria).

This has come at a convenient time in Australia’s growth profile. Business investment expenditure is still low as the end of the mining downturn drags on, housing construction is slowing and consumer spending growth remains modest (see chart below).

So, the recent uplift in government spending has been offsetting much of the weakness across other parts of the economy. But, it won’t last forever. How much longer can the strength in government spending last? And what happens as the pipeline of infrastructure projects dwindles?

How is infrastructure provided in Australia?

It is helpful to understand how infrastructure is provided in Australia. Infrastructure spending is mainly undertaken by the states. States obtain funding for infrastructure spending from state-based sources (largely taxation) but also rely on Commonwealth Government grants. Recently, states have also been utilising the federal government’s asset recycling scheme.

Asset recycling was a federal government program introduced in the 2014 Budget that incentivised the states and territories to privatise their assets (particularly underperforming or surplus assets) and use the proceeds to fund new infrastructure, with the federal government providing a financial incentive for the sale.

This initiative has now finished, and New South Wales and Victoria were the two main adopters of the program.

Besides providing grants and promoting asset recycling to the states, the federal government can also push through infrastructure spending by:

- Direct spending to acquire physical assets which is generally done for defence spending. This spending adds to the budget deficit which is difficult at the moment given pressures to meet the 2021 budget surplus target.

- Direct spending to acquire financial assets. This spending takes the form of loan or equity contribution to a separately established third party, which is eventually sold to the private sector. This transaction appears on the cash flow statement as an investment but doesn’t impact the underlying cash balance.

What is the outlook for infrastructure investment in Australia?

Based on state and federal budget plans for capital spending, infrastructure investment growth will remain strong over 2018, and will then taper off (see chart below).

Federal government grants to the states are still high, state budgets have been bolstered by payments from asset recyling initatives and states (particularly in New South Wales and Victoria) have been collecting significant stamp duty payments from a booming property market. In the 2017 budget, the federal government also committed to spending directly through equity financing to build the Melbourne to Brisbane Inland Rail and Western Sydney Airport.

What will be the impact on employment?

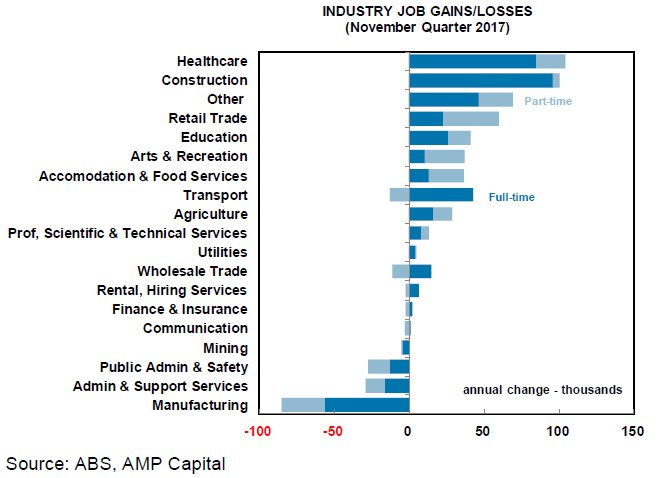

Infrastructure investment is an employment-intensive industry, similar to residential construction. This is clear in the latest employment data with very strong growth in construction jobs (see chart below), particularly in the full-time space.

Growth in infrastructure spending over 2018 will add to gains in employment, particularly across the construction, transport and professional services space.

What about after the end of the infrastructure boom?

The current pipeline of infrastructure projects will slow significantly in mid-2019, which will be a hit to growth and employment. This means that other parts of the economy will need to be stronger to offset a slowing contribution from the government sector.

Non-mining private business investment growth is expected to lift over the next two years given decent earnings growth forecasts and improving outcomes from business surveys. Export growth should remain solid from strong global growth, but a potential slowdown in the Chinese economy is a risk.

As well, the consumer may come under pressure if interest rates move too high in 2019. We expect the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) to start lifting interest rates at the end of this year, starting with one hike. The RBA will need to tread carefully in hiking interest rates in 2019, ensuring that the interest rate-sensitive parts of the economy do not come under significant pressure, especially if the Australian dollar is still elevated.

Will the US lift infrastructure spending?

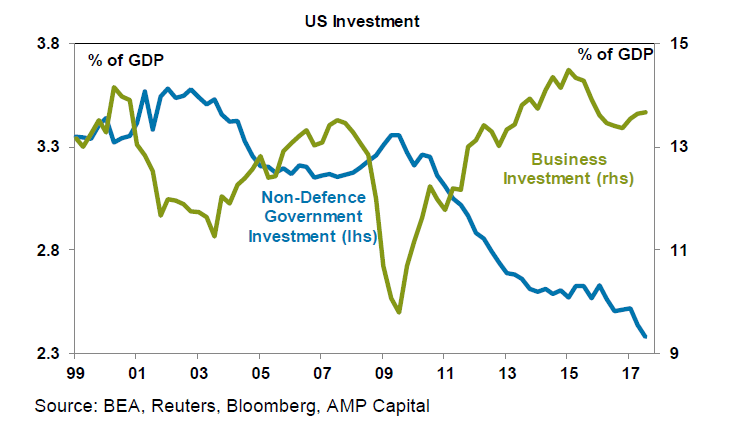

The recent focus in the US has been on tax reform. And the cut to corporate and household taxes (and other corporate write-offs for business investment) will boost US GDP growth in 2018 and 2019 (we expect GDP growth of 2.6% in 2018 from 2.3% in 2017). Infrastructure spending was a focal point in pre-election talk from President Trump and has been mentioned again recently. Infrastructure investment has been slipping in the US (see chart below). But additional government spending at a time when GDP growth is already growing above its potential may cause unnecessary upward pressure on inflation.

Talk from the Republican party has indicated that there is a desire to generate around $1.5trillion in federal, state and local government infrastructure spending. Given the pressure to keep the budget deficit under control, a lot of this funding would need to be pursued via arrangements like public-private partnerships.

The Republicans would want to push through infrastructure investment before the mid-term elections.

Implications for investors

A substantial pipeline of infrastructure projects will keep Australian growth buoyant over 2018 (we expect growth of 2.7% in 2018 from 2.3% in 2017) and into early 2019. But, government spending will taper off in mid-2019 once projects finish construction which will drag on growth and employment.

Business investment growth will be stronger in 2019 and will provide an offset. But, expected higher interest rates next year may hit consumer spending. The RBA will need to tread carefully in lifting interest rates.