Key points

- The Australian housing market remains far more complicated than optimists & doomsters portray it to be.

- Yes, it’s expensive and heavily indebted but talk of mortgage stress is overstated & it’s been undersupplied.

- The combination of rate cuts, the election and a modest regulatory relaxation have helped turn property prices back up, but the upswing is likely to be constrained.

Introduction

After the biggest fall in at least 40 years – with a 10.2% top to bottom fall between September 2017 and June this year - average capital city home prices have turned up again. I thought prices would fall further with a 15% top to bottom fall led by around 25% falls in Sydney and Melbourne. But the facts changed from May – with the election removing the threat to negative gearing & the capital gains tax discount, earlier than expected interest rate cuts & a relaxation of APRA’s 7% interest rate test all pushing prices up again. So, where to from here?

Extreme property views

There are basically two extreme views amongst “property experts”. On the one hand, some real estate spruikers still wheel out the old “property will double every seven years” line. On the other hand, property doomsters say it’s hugely overvalued and overindebted with massive mortgage stress and so a 40% or so crash is inevitable. The trouble with the former is that implies home price growth of 10.3% pa, so even if wages growth picks up to 3.5% (a big ask!) it implies that the average price to income ratio of Australian housing will rise to around 9 times over the next 7 years from around 6 times now and in 14 years’ time it will be 14 times! The trouble with the doomsters is that they’ve been saying that for 15 years and we’re still waiting for the crash. In between, first home buyers are wondering why it’s so hard to do what my and my parent’s generation took for granted: be part of the Aussie dream with a quarter acre block. The reality is it’s far more complicated than these extremes. Here’s seven stylised “facts” regarding Australian property.

First – it’s expensive

This has been the case since early last decade and remains so despite the recent correction in prices:

- According to the 2019 Demographia Housing Affordability Survey the median multiple of house prices to income is 5.7 times in Australia versus 3.5 in the US and 4.8 in the UK. In Sydney it’s 11.7 times & Melbourne is 9.7 times.

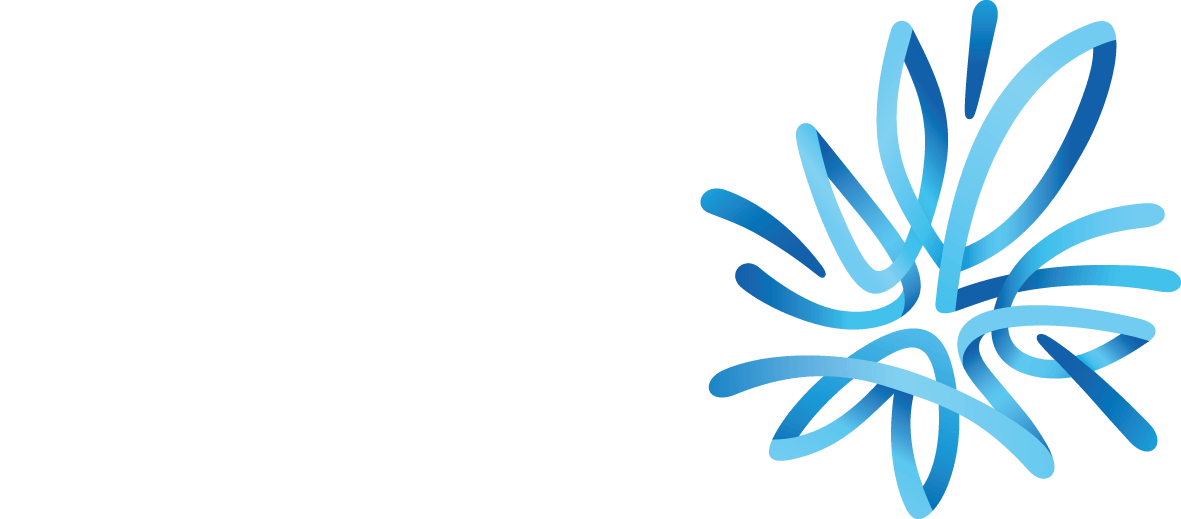

- The ratios of house prices to incomes and rents relative to their long-term averages are at the high end of OECD countries.

- The surge in prices relative to incomes has seen household debt relative to household income rise from the low end of OECD countries 25 years ago to the high end now.

These things arguably make residential property Australia’s Achilles heel. But that’s been the case for 15 years or so now.

Second – it’s diverse

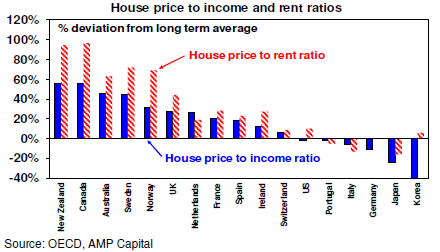

While it’s common to refer to “the Australian property market”, in reality there is significant divergence between cities. This divergence has been extreme over the last five years with Perth and Darwin seeing large price falls in response to the end of the mining investment boom, as other cities rose.

The divergence is also evident in gross rental yields that range from 8.7% in regional WA units to 3.1% in Sydney houses.

Third – talk of mortgage stress is overstated

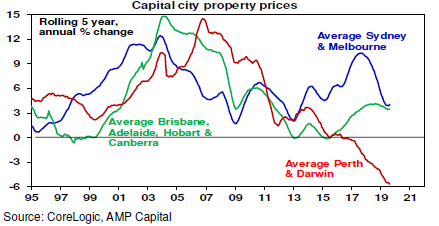

Headlines of excessive mortgage stress have been common for over a decade now. There is no denying housing affordability is poor, household debt is high and some households are suffering significant mortgage stress. But most borrowers appear to be able to service their mortgages. And despite some seeing negative equity and a significant proportion of borrowers switching from interest only to principle & interest loans (which has seen interest only loans drop from nearly 40% of all loans to 23%) there has been no surge in forced sales and non-performing loans. Non-performing mortgages have increased but remain low at around 0.9%. While Australia saw a deterioration in lending standards with the last boom, it was nothing like other countries saw prior to the GFC. Much of the increase in debt has gone to older, wealthier Australians, who are better able to service their loans. Low doc loans are trivial in Australia and the proportion of high loan to valuation ratio loans has fallen as has the proportion of interest only loans.

Fourth – it’s been chronically undersupplied

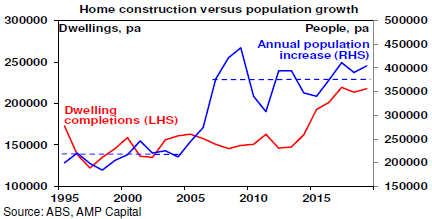

Annual population growth since mid-last decade has averaged 373,000 people compared to 217,000 over the decade to 2005, which requires roughly an extra 75,000 homes per year. Unfortunately, the supply of dwellings did not keep pace with the population surge (see the next chart) so a massive shortfall built up driving high home prices. Thanks to the surge in unit supply since 2015 this is now being worked off, but it follows more than a decade of accumulated undersupply which is the main reason why housing has remained relatively expensive in Australia. Not tax breaks or low rates – all of which exist in other countries with far more affordable housing!

Fifth – house prices go up and down

After several episodes of price declines ranging from 5 to 10% across various cities over the last 15 years and 15%, 21% and 31% for Sydney, Perth and Darwin respectively in recent years home buyers should be under no illusion that prices only go up.

Sixth – the housing market remains rate sensitive

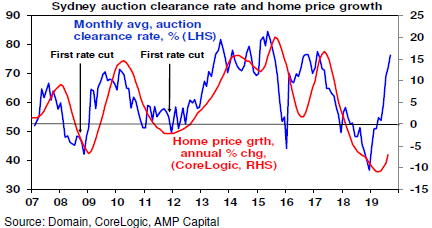

While it varies from city to city, despite much scepticism recent rate cuts have helped push up the property market again.

Finally – house price crashes are not easy to forecast

The expensive nature of Australian property and associated high debt levels have seen calls for a property crash pumped out repeatedly over the last 15 years. In 2004, The Economist magazine described Australia as “America’s ugly sister” thanks in part to soaring property prices. Property crash calls were wheeled out repeatedly after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) with one commentator losing a high-profile bet that prices could fall up to 40%. In 2010, a US newspaper, The Philadelphia Trumpet, warned that “Los Angelification” (referring to a 40% slump in LA home prices around the GFC) will come to Australia. Similar calls were made a few years ago by a hedge fund researcher and a hedge fund: “The Australian property market is on the verge of blowing up on a spectacular scale."

Over the years these crash calls have often made it on to 60 Minutes and Four Corners.

But our view remains that to get a national housing crash – as opposed to periodic falls in some cities – we need much higher unemployment, much higher interest rates and/or a big oversupply. But while the risk of recession has increased it remains unlikely, aggressive rate hikes are most unlikely and while property supply still has more upside it’s unlikely to lead to a big oversupply as approvals to build new dwellings are now falling. As we have seen for years now overvaluation and high debt on their own are not enough to bring on a crash.

So where to now?

The rebound in buyer interest since May has seen auction clearance rates in Sydney and Melbourne rise to around 75% and prices lift nearly 2%, albeit other cities are mixed.

This has so far come on low volumes, but they now look to be rising. Our base case is that house price gains will be far more constrained than the 10-15% implied by current auction clearance rates. Compared to past cycles debt to income ratios are much higher, bank lending standards are tighter, the supply of units has surged with more to come and this has already pushed Sydney’s rental vacancy rate above normal levels and unemployment is likely to drift up as economic growth remains soft. So, we don’t expect to see a return to boom time conditions and see constrained gains through 2020 – eg around 5% or so. There are three key things to watch:

- The Spring selling season – if auction clearances remain elevated as listing pick up then it will be a positive sign that the pick-up in the property market has legs.

- Housing finance commitments – these have bounced but will have to pick up a lot further to get 10-15% price rises.

- Unemployment – if it picks up significantly in response to slow economic growth then it will be a big constraint on house prices and could result in another leg down in prices.

We don’t see the rebound in the Sydney and Melbourne property markets as a barrier to further monetary easing, but it may reduce the need as it turns the wealth effect from negative to positive. And if it continues to gather pace then expect a tightening of the screws again from bank regulators.

Implications for investors

Over long periods of time residential property provides a similar return to shares (at around 11% pa) but it offers good diversification as it performs well at different times to shares so it has a role to play in investors’ portfolios. The pull back in prices in several cities in the last few years provides opportunities for investors, but just bear in mind that rental yields remain relatively low in Sydney and Melbourne and be wary of areas where there is still a lot of new units to hit. There is probably better value to be found in regional centres and Perth, and Brisbane looks attractive in offering reasonable yields, a low vacancy rate and improving population growth.